- Home

- Mark Chadbourn

The Silver Skull Page 3

The Silver Skull Read online

Page 3

“This is it, then,” he said quietly.

“Blood has been spilled. Lives have been ruined. The clock begins to tick.”

“I did not think it would be so soon. Why now?”

“You will receive answers shortly. We knew it was coming.” After a pause, he said gravely, “William Osborne is dead, his eyes put out, his bones crushed at the foot of the White Tower.”

“Death alone was not enough for them.”

“He did it to himself.”

Will considered Osborne’s last moments and what could have driven him to such a gruesome end.

“Master Mayhew survived, though injured,” Walsingham continued.

“You have never told me why they were posted to the Tower.”

Walsingham did not reply. The carriage trundled towards London Bridge, the entrance closed along with the City’s gates every night when the Bow Bells sounded.

Echoing from the river’s edge came the agonised cries of the prisoners chained to the posts in the mud along the banks, waiting for the tide to come in to add to their suffering. Above the gates, thirty spiked decomposing heads of traitors were a warning of a worse fate to those who threatened the established order.

As the driver hailed his arrival, the gates ground open to reveal the grand, timber-framed houses of wealthy merchants on either side of the bridge. The carriage rattled through without slowing and the guards hastily closed the gates behind them to seal out the night’s terrors.

The closing of the gates had always signalled security, but if the City’s defences had been breached there would be no security again.

“A weapon of tremendous power has fallen into the hands of the Enemy,” Walsingham said. “A weapon with the power to bring about doomsday. These are the days we feared.”

HAPTER 2

n the narrow, ancient streets clustering hard around the stone bulk of the Tower of London, the dark was impenetrable, threatening, and there was a sense of relief when the carriage broke out onto the green to the north of the outer wall where lanterns produced a reassuring pool of light.

Standing in ranks, soldiers waited to be dispatched by their commander in small search parties fanning out across the capital. Robert Dudley, the earl of Leicester, strutted in front of them, firing off orders. Though grey-bearded and with a growing belly, he still carried the charisma of the man who had entranced Elizabeth and seduced many other ladies of the court.

A crowd had gathered around the perimeter of the green, sleepy-eyed men and women straggling from their homes as word spread of the activity at the Tower. Will could see anxiety grow in their faces as they watched the grim determination of the commanders directing the search parties. Fear of the impending Spanish invasion ran high, and in the feverish atmosphere of the City tempers were close to boiling over into public disturbance. Spanish spies and Catholic agitators were everywhere, plotting assassination attempts on the queen and whipping up the unease in the inns, markets, and wherever people gathered and unfounded rumours could be quickly spread.

Ignoring the crowd’s calls for information about the disturbance, Walsingham guided Will to the edge of the green where a dazed, badly bruised, and bloody Mayhew squatted.

“England’s greatest spy,” Mayhew said, forming each word carefully, as he nodded to them.

“Master Mayhew. You have taken a few knocks.”

“But I live. And for that I am thankful.” Hesitating, he glanced at the White Tower looming against the night sky. “Which is more than can be said for that fool Osborne.”

“You were guarding the weapon,” Will surmised correctly.

“A weapon,” Mayhew exclaimed bitterly. “We thought it was only a man. A prisoner held in his cell for twenty years.”

Walsingham cast a cautionary glare and they both fell silent. “There will be time for discussion in a more private forum. For now, all you need know is that a hostile group has freed a prisoner and escaped into the streets of London. The City gates remain firmly closed …” He paused, choosing his words carefully. “Although we do not yet know if they have some other way to flee the City. The prisoner has information vital to the security of the nation. He must be found and returned to his cell.”

“And if he is not found?” Will enquired.

“He must be found.”

The intensity in Walsingham’s voice shocked Will. Why was one man so important—they had lost prisoners before, though none from the Tower—and how could he also be considered a weapon?

“Your particular skills may well be needed if the prisoner is located,” Walsingham said to Will before turning to Mayhew. “You must accompany me back to the Palace of Whitehall. I would know the detail of what occurred.”

Mayhew looked unsettled at the prospect of Walsingham’s questioning, but before they could leave, the principal secretary was summoned urgently by Leicester, who had been in intense conversation with a gesticulating commander.

“They call your name.” Mayhew nodded to the crowd. “Your reputation has spread from those ridiculous pamphlets they sell outside Saint Paul’s.”

“It serves a purpose,” Will replied.

“Would they be so full of admiration if those same pamphlets had called you assassin, murderer, corruptor, torturer, liar, and deceiver?” Mayhew’s mockery was edged with bitterness.

“Words mean nothing and everything, Matthew. It is actions that count. And results.”

“Ah, yes,” Mayhew said. “The end results justify the means. The proverb that saves us all from damnation.”

Will was troubled by Mayhew’s dark mood, but he put it down to the shock of the spy’s encounter with the Enemy. His attention was distracted by Walsingham, who, after listening intently to Leicester, summoned Will over. “We may have something,” he said with an uncharacteristic urgency. “Accompany Leicester, and may God go with you.”

At speed, Leicester, Will, and a small search party left the lights of the green. Rats fled their lantern by the score as they made their way into the dark, reeking streets to the north, some barely wide enough for two men abreast.

“On Lord Walsingham’s orders, I attempted to seek the path the Enemy took from the Tower,” Leicester said, as they followed the lead of the soldier Will had seen animatedly talking to Leicester. “They did not pass through the Traitors’ Gate and back along the river, the route by which they gained access to the fortress. None of the City gates were disturbed, according to the watch. And so I dispatched the search parties to the north and west.” He puffed out his chest, pleased with himself.

“You found their trail?”

“Perhaps. We shall see,” he replied, but sounded confident.

In the dark, Will lost all sense of direction, but soon they came to a broader street guarded by four other soldiers, from what Will guessed was the original search party. They continually scanned the shadowed areas of the street with deep unease. Will understood why when he saw the three dead men on the frozen ruts, their bodies torn and broken.

Kneeling to examine the corpses, Will saw that some wounds looked to have been caused by an animal, perhaps a wolf or a bear, others as if the victims had been thrown to the ground from a great height. They carried cudgels and knives, common street thugs who had surprised the wrong marks.

“Were these men killed by the Enemy?” Leicester asked, his own eyes flickering towards the dark.

Ignoring the question, Will said, “Three deaths in this manner would not have happened silently. Someone must have heard the commotion, perhaps even saw in which direction the Enemy departed. Search the buildings.”

As Leicester’s men moved along the street hammering on doors, blearyeyed men and women emerged, cursing at being disturbed until they were roughly dragged out and questioned by the soldiers.

Will returned to the bodies, concerned by the degree of brutality. In it, he saw a level of desperation and urgency that echoed the anxiety Walsingham had expressed; here was something of worrying import that would have cons

equences for all of them.

His thoughts were interrupted by a cry from one of Leicester’s men who was struggling with an unshaven man in filthy clothes snarling and spitting like an animal. Three soldiers rushed over to help knock him to the frosty street.

“He knows something,” the man’s captor said, when Will came over.

“I saw nothing,” the prisoner snarled, but Will could see the lie in his furtive eyes.

“It would be in your best interests to talk,” Leicester said, but his exhortation was delivered in such a courtly manner that it was ineffectual. The man spat and tried to wrestle himself free until he was cuffed to the ground again.

Leicester turned to Will and said quietly, “We could transport him back to the Tower. I gather Walsingham has men there who could loosen his tongue.”

“If we delay, the Enemy will be far from here and their prize with them,” Will said. “The stakes are high, I am told. We cannot risk that.” He hesitated a moment as he examined the man’s face and then said, “Let me speak with him. Alone.”

“Are you sure?” Leicester hissed. “He may be dangerous.”

“He is dangerous.” Will eyed the pink scars from knife fights that lined the man’s jaw. “I am worse.”

Leicester’s men manhandled the prisoner back into his house, and Will closed the door behind him after they left. It was a stinking hovel with little furniture, and most that was there looked as if it had been stolen from wealthier premises. The prisoner hunched on the floor by the hearth, pretending to catch his breath, and then threw himself at Will ferociously. Sidestepping his attack, Will crashed a fist into his face. Blood spurted from his nose as he was thrown back against a chair, but it did not deter him. He pulled a knife from a chest beside the fireplace, only to drop it when Will hit him again. As he scrambled for the blade, Will stamped his boot on the man’s fingers, shattering the bones. The man howled in pain.

Dragging the man to his feet, Will threw him against the wall, pressing his own knife against his prisoner’s throat. “England stands on the brink of war. The queen’s life is threatened daily. A crisis looms for our country,” Will said. “This is not the time for your games.”

“This is not a game!” the man protested. “I dare not speak! I fear for my life!”

Will pressed the tip of his knife a shade deeper for emphasis. “Fear me more,” he said calmly. “I will whittle you down a piece at a time—fingers, nose, ears—until you choose to speak. And you will choose. Better to speak now and save yourself unnecessary suffering.”

Once the rogue had seen the truth in Will’s eyes, he nodded reluctantly.

“You saw what happened out there?” Will asked.

“I was woken by the sounds of a brawl. From my window, I saw a small group of cloaked travellers set upon by a gang of fifteen or more.”

“Cutthroats?”

The man nodded.

“Fifteen? At this time? They cannot find much regular trade in this area to justify such a number.”

“It seemed they knew the travellers would be passing this way. They lay in wait. Some of them emerged only after the battle had commenced.”

This information gave Will pause, but his prisoner was too scared to be telling anything but the truth. “Who were these cutthroats?”

The man shook his head. “I did not recognise them. But if they find I spoke of them they will be back for me!”

“I would think they now have more important things on their minds. What happened?”

“They surprised the travellers.” He hesitated, not sure how much he should say. “The travellers …” He swallowed, looked like he was about to be sick. “They turned on the cutthroats. I had to look away. I saw no more.”

“The faces of the travellers?”

He shook his head. “They moved too fast. I … I saw no weapons. Only the slaughter of three victims. It was madness! The other cutthroats fled—”

“And the travellers continued on their way?”

“One of them was different … his head glowed like the moon.”

“What do you mean?”

The man began to stutter and Will had to wait until he calmed. “I do not know … it was a glimpse, no more. But his head glowed. And in the confusion, two of the cutthroats grabbed him and made good their escape into the alleys. He went with them freely, as though he had been a prisoner of the travellers.”

“And the travellers gave pursuit?”

“Once they saw he was missing … a minute, perhaps two later. By then, their chances of finding him would have been poor.”

The frightened man had no further answers to give. Out in the street, Will summoned Leicester away from his men’s ears.

“The prize the Enemy stole from the Tower was in turn taken from them by a band of cutthroats,” Will told him. “Put all your men onto the streets of London. This threat may now have gone from bad to worse.”

HAPTER 3

ill clung on to the leather straps as the sleek black carriage raced towards the Palace of Whitehall, a solitary ship of light sailing on the sea of darkness washing against London’s ancient walls.

Lanterns hung from the great gates and along the walls. From diamondpane windows, candles glimmered across the great halls and towers, the chapels, wings, courtyards, stores, meeting rooms, and debating chambers, and in the living quarters of the court and its army of servants. At more than half a mile square, it was one of the largest palaces in the world, shaped and reshaped over three hundred years. Hard against the Thames, it had its own wharf where barges were moored to take the queen along the great river and where vast warehouses received the produce that kept the palace fed. Surrounding the complex of buildings were a tiltyard, bowling green, tennis courts, and formal gardens, everything needed for entertainment.

The palace looked out across London with two faces: at once filled with the sprawling, colourful, noisy pageantry of royalty, of a court permanently at play, of music and masques and arts and feasting, of romances and joys and intrigues, a tease to the senses and a home to lives lost to a whirl that always threatened to spin off its axis; and a place of grave decisions on the affairs of state, where the queen guided a nation that permanently threatened to come apart at the seams from pressures both within and without. Whispers and fanfares, long, dark shadows and never-extinguished lights, conspiracies and open rivalries. The palace was a puzzle that had no solution.

The carriage came to a halt under a low arch in a cobbled courtyard so small that the buildings on every side kept it swathed in gloom even during the height of noon. Few from the court even knew it existed, or guessed what took place behind the iron-studded oak door beside which two torches permanently hissed. The jamb too was lined with iron, as was the step.

The door swung open at Will’s knock and admitted him to a long, windowless corridor lit by intermittent pools of lamplight. The silent guard closed the door and slid six bolts home. Will’s echoing footsteps followed him up one flight of a spiral staircase into the Black Gallery, a large panelled hall. Heavy drapes covered the windows, but it was lit by several lamps and a few flames danced along a charred log in the glowing ashes of the large stone fireplace.

A long oak table filled the centre of the hall, covered with maps, and at the far end sat Mayhew, one louche leg over the arm of his chair. His head was tightly bound in a bloodstained cloth and his left arm was in a sling. He was taking deep drafts of wine from a goblet, and appeared drunk.

Will always found Mayhew difficult. He was hard, in the manner of all spies forced to operate in a world of deceit, and had little patience for his fellows, more concerned with the latest courtly fashions. He liked his wine, too, when he was not working, but he was a sullen, sharp-tongued drunk.

Walsingham emerged at the sound of Will’s voice, his features drawn. He listened intently as Will told him about the attack on the Enemy and their loss of the mysterious prisoner from the Tower, but he passed no comment.

“The queen has bee

n informed?” Will asked once he had finished his account.

“I advised her myself,” Walsingham replied. “She is fully aware of the magnitude of what lies ahead.”

“Which is more than I am.” Will expected a terse response, but the principal secretary was distracted by the sound of slamming doors and rapidly marching feet.

Through a door at the far end of the hall, two guards escorted a man wearing a purple cloak and hood that shrouded his features. The guards retreated as the new arrival strode across the room to the fire.

“I can never get warm these days,” he said, holding out aged hands to the flames. “It is one of the prices I pay.”

The man threw off his hood to reveal a bald pate and silvery hair at the back falling over his collar. As he turned to face the room, fierce grey eyes shone with a coruscating intellect and a sexual potency that belied his sixty-odd years.

“Dee!” Mayhew visibly started in his chair, slopping wine in his lap.

Dr. John Dee cast a disinterested eye over Mayhew. “You have not aged well,” he said, before slipping off his cloak and throwing it over a chair.

To the outside world, Dee was a respected scholar and founding fellow of Trinity College in Cambridge who had been an advisor and tutor to the queen, whose General and Rare Memorials Pertaining to the Perfect Arte of Navigation had established a vision of an English maritime empire and defined the nation’s claims upon the New World. Few knew that Dee had been instrumental in helping Walsingham establish the extensive spy network, providing intelligence and guidance as well as designing many of the tools the spies used to ply their dangerous trade.

But Will had heard other rumours: that Dee had turned his back upon his studies of the natural world for black magic and scrying and attempts to commune with angels. Will had presumed this had contributed to Dee’s fall from favour—for five years he had been absent from the court in Central Europe. The last any of them had heard of him was in Bohemia a year ago.

The Hounds of Avalon tda-3

The Hounds of Avalon tda-3 The Devil's Looking-Glass soa-3

The Devil's Looking-Glass soa-3 Always Forever taom-3

Always Forever taom-3 The Scar-Crow Men

The Scar-Crow Men Destroyer of Worlds kots-3

Destroyer of Worlds kots-3 Jack of Ravens kots-1

Jack of Ravens kots-1 The Devil in Green

The Devil in Green World's End

World's End Darkest Hour (Age of Misrule, Book 2)

Darkest Hour (Age of Misrule, Book 2) Destroyer of Worlds

Destroyer of Worlds The Ice Wolves

The Ice Wolves The Devil soa-3

The Devil soa-3 Always Forever

Always Forever World's End (Age of Misrule, Book 1)

World's End (Age of Misrule, Book 1) The Scar-Crow Men soa-2

The Scar-Crow Men soa-2 Darkest hour aom-2

Darkest hour aom-2 The Devil's Looking-Glass

The Devil's Looking-Glass The Silver Skull

The Silver Skull World's end taom-1

World's end taom-1 Jack of Ravens

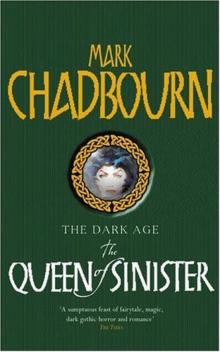

Jack of Ravens The Queen of Sinister

The Queen of Sinister